Habit Calendar

This post is about an LED “calendar” I created to help track and promote habits over the course of a year. This project was scratch built from the ground up. Starting from circuit and PCB design to full software feature implementation. I’m proud to say it has been succesfully completed! All of the projects files can be found here.

Introduction:

A little while ago, I came across Simone Giertz’s Everyday Calendar and was inspired to design and build my own for fun! The product is intended to track a habit over the course of a year, with one illuminated light representing a day in which the habit was done. It’s a wonderful idea and a beautiful product, and Simone is awesome, so I encourage you to support her work! I will be getting my own sometime soon!

The fun of this project is that there are boundless, unique ways to design it. You don’t even need electronics at all. Any way you can track something is a way to make an implementation. The problem with this project is that there are boundless, unique ways to design it. You don’t even need electronics at all. Any way you can track something is a way to make an implementation.

The design goal with this one was to keep it very simple and very cheap. In the end, I’m not sure I’m satisfied with where I ended in either category, but constantly revisiting these constraints kept me from going off into crazy land, which was all too easy to find myself headed for.

The problem with cost is that when you need 365 representations for something, it adds up! Certainly, you can find ways to scale it down, but I really liked the idea of an entire year, one illuminating light per day, and one unique control per day. Each time you get to hit that button, it should have a simple and rewarding feeling. Having a complex input method wouldn’t provide that same satisfaction. One input and one light to represent each day for a full year. That was the requirement.

Designs:

The first complete design I had is by far the cheapest and simplest. It really didn’t get any better in either dimension than this. For $5, you can get 500 through-hole LEDs. For $10, you can get 500 through-hole resistors. And for $20, you can get 400 latching buttons. Latching buttons work such that when the button is pressed once, it remains in the connected state. When the button is pressed again, it remains in the disconnected state. Simple. This design is great because it requires zero software at all. Zero! It is purely a hardware solution. It even holds its state through power cycles and for roughly $35, too! The only problem is it requires soldering a connection from power to the button, to the resistor, to the LED, and to the ground. And that has to happen for each of the 365 days of the year. So, a minimum of 365*4=1460 soldering joints. That’s a lot of soldering to do.

I have all the components but am waiting for a rainy day to sit down and solder them all up. Someday, I’ll get to it… Maybe.

With the unlimited design opportunities, I found myself thinking up more designs often. I couldn’t help myself. I felt there was a pretty good solution somewhere that could still meet the cheap and simple criteria with a board I designed and sent off for manufacturing and assembly at JLCPCB.

The cool and interesting thing about this approach is the boards would have to be tiled to scale to meet the requirements. Manufacturing large PCBs would be cost-prohibitive. I love modular design, so this aspect was something I was excited about!

I could, of course, just make that first design into a board and have them manufacture it, but the buttons were more expensive, and if I was going to have a board assembled, I might as well make it something cooler, right? A little added complexity wouldn’t be too bad, right?

I wanted to use the cheapest components available, so I looked for the most inexpensive LEDs, resistors, and buttons. There’s nothing particularly interesting about these components other than there are 365 of them, and there needs to be something to read a momentary push button and drive current through a resistor. That logic adds complexity.

Initially, I looked for microcontroller GPIO expanders, but those are way too expensive at scale. Then I looked at cheap microcontrollers, but those are also too expensive at scale, and scaling the power requirements through the microcontroller limited the number of GPIOs that could be used as output from a single MCU or added more circuitry, which again adds up at a multiple of 365.

Then, I looked at serial to parallel and parallel to serial shift registers. This is a common technique for GPIO expansion. In fact, this is how the Everyday Calendar from Simone Giertz was designed.

It is a fine solution that requires a master controller to coordinate everything. This makes software rather straightforward. And the components are relatively cheap. The cheapest implementation I found. So, I sketched out a quick design.

And I wasn’t excited about it.

I felt there was something more unique that could be done or even cheaper. And really, I wasn’t fond of the idea of a master controller.

So I kept thinking about it.

And then, I went back to the microcontroller idea. Two new cheap MCUs were being offered that were creating quite a buzz recently. These chips were the RISC-V Based CH00 and the ARM Cortex M0+ PY32. Though there are microcontrollers even cheaper than this, they are not reprogrammable and have very limited amounts of RAM. These two new microcontrollers contained rewritable flash, which was helpful for development and would probably be necessary to keep the state between power cycles.

After looking further into the parts, even though the CH00 was cheaper, the nonstandard toolchain threw me off. And to my delight, the PY32 sounded like it worked in a normal environment. An invaluable overview of the PY32 family, developer experience, and comparison with CH00 can be found at Jay Carlson’s website

The PY32 comes in a TSSOP20 package with 18 GPIO pins for $0.11. That’s less than a cent per pin, which is even better than the shift register design!

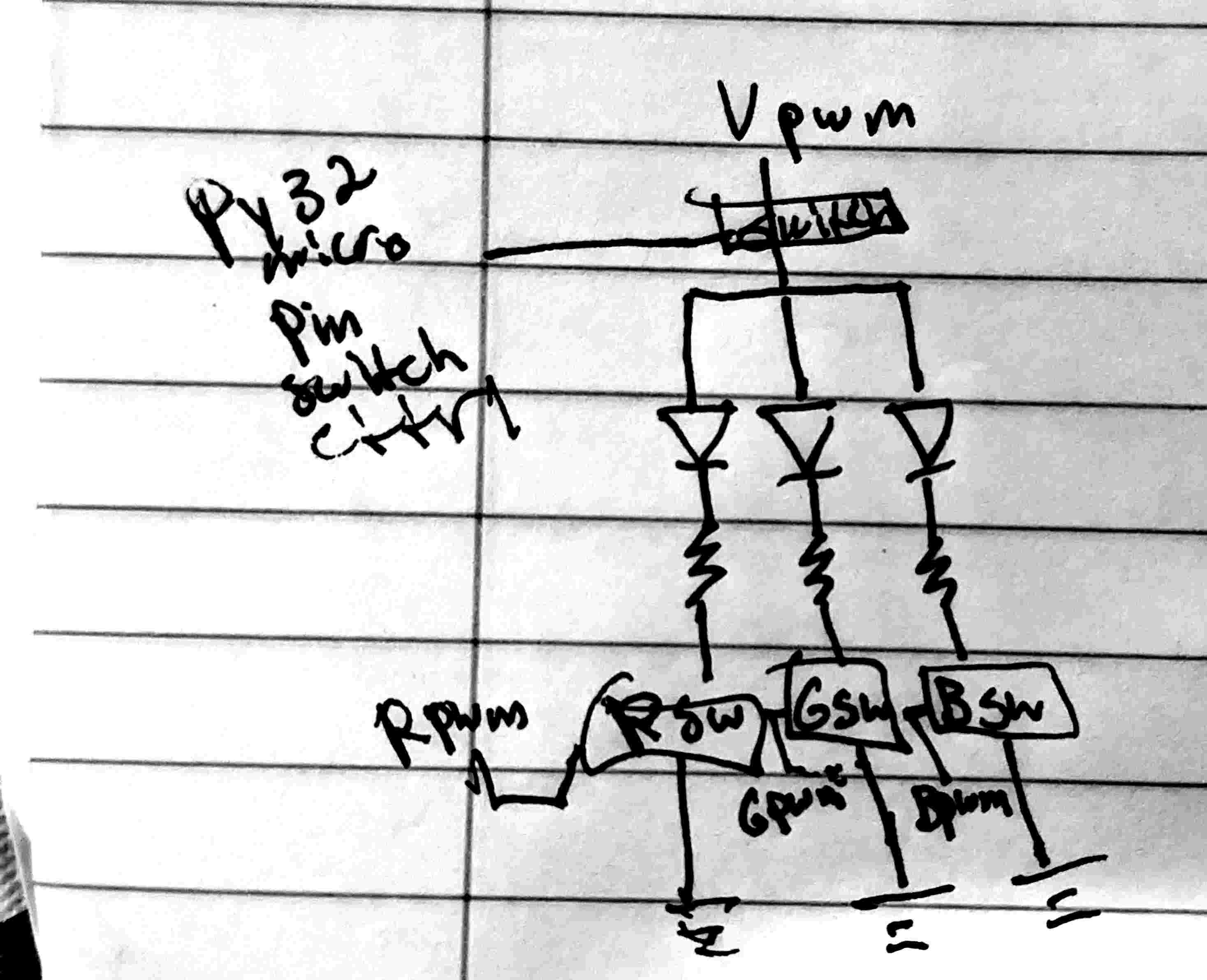

I anticipated needing 365 inputs and 365 outputs. And then I started designing, and I hit a gigantic wall. I could not decide on what color LED to use. So, I came up with the “clever” solution to just use an RBG LED and be able to choose a color at my whim. Except that that adds infinitely more complexity and cost. But I designed it anyway. (The first draft rough sketch schematic can be seen below)

I needed to add mosfets to control the power because the microcontroller would max out rather quickly, trying to power more LEDs. And more GPIO because there were more LEDs to illuminate. And it was getting even more expensive! And probably that master controller was coming back. And then I circled around and went into WS2812b land. A single GPIO to drive all the LEDs? Any color and brightness I want? No added circuitry? Still pretty dang cheap. Sounded like a win.

I probably should’ve just picked a color and kept it simple. But I went with the WS2812b, PY32 combo.

Hardware Design:

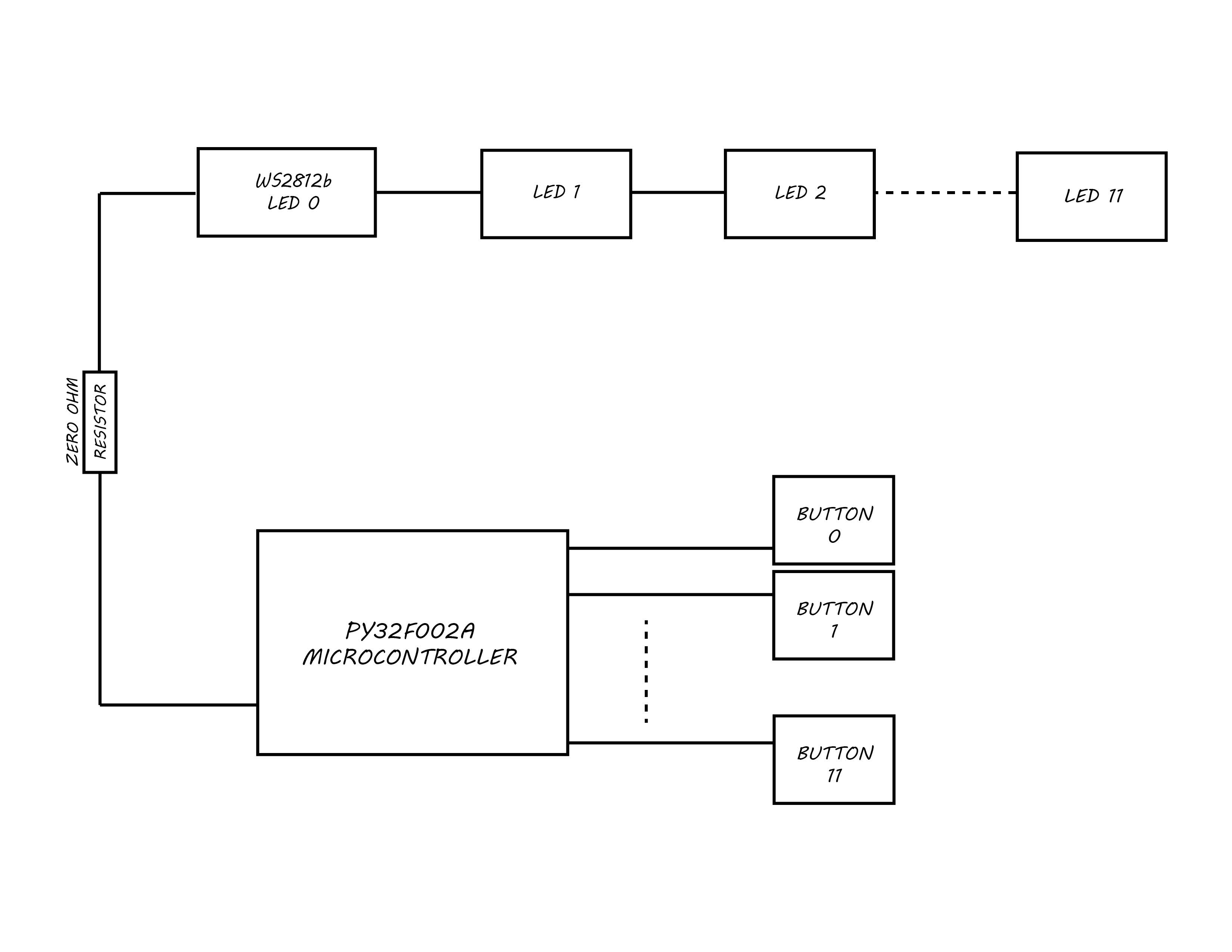

A simple block diagram can be seen here:

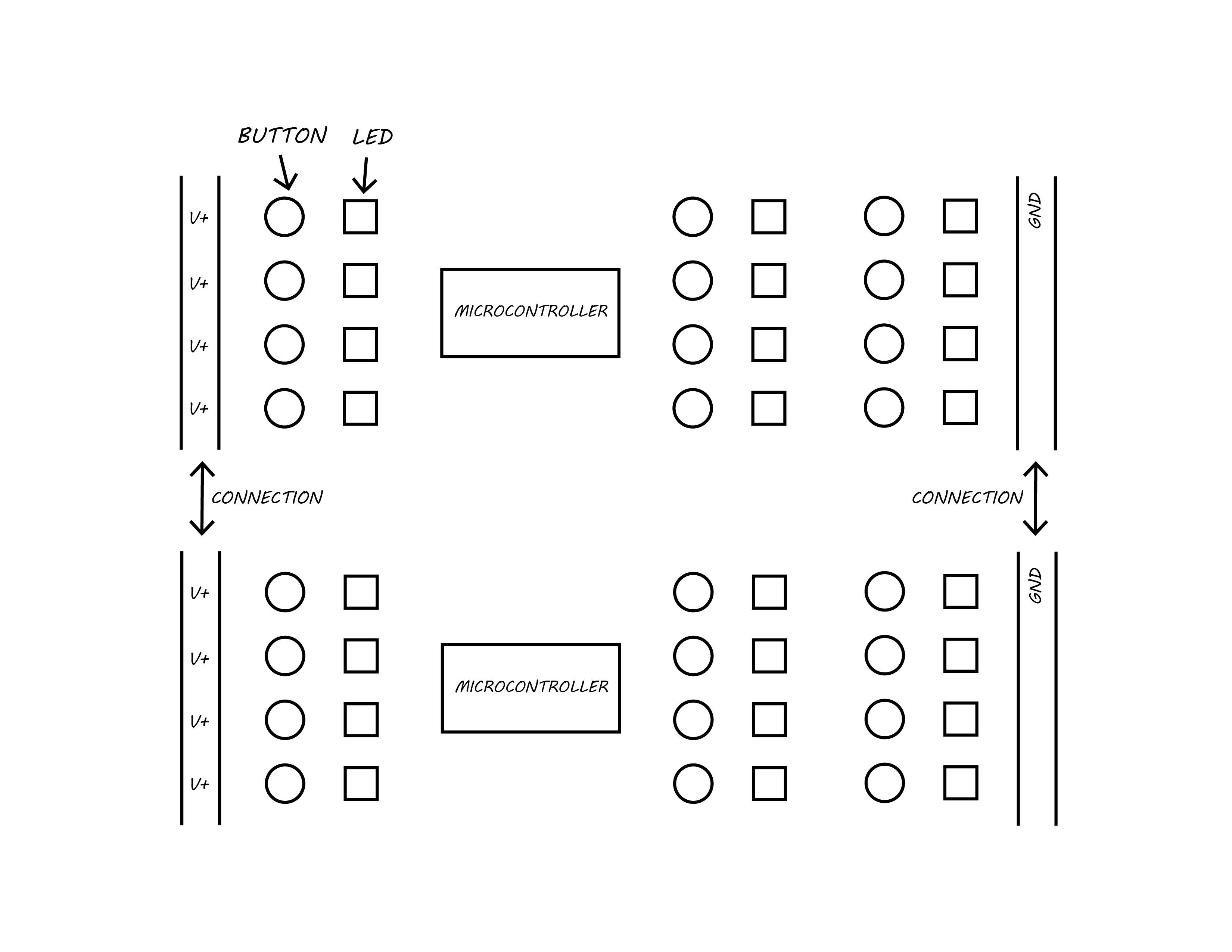

Along with the tiled variant for the full calendar here:

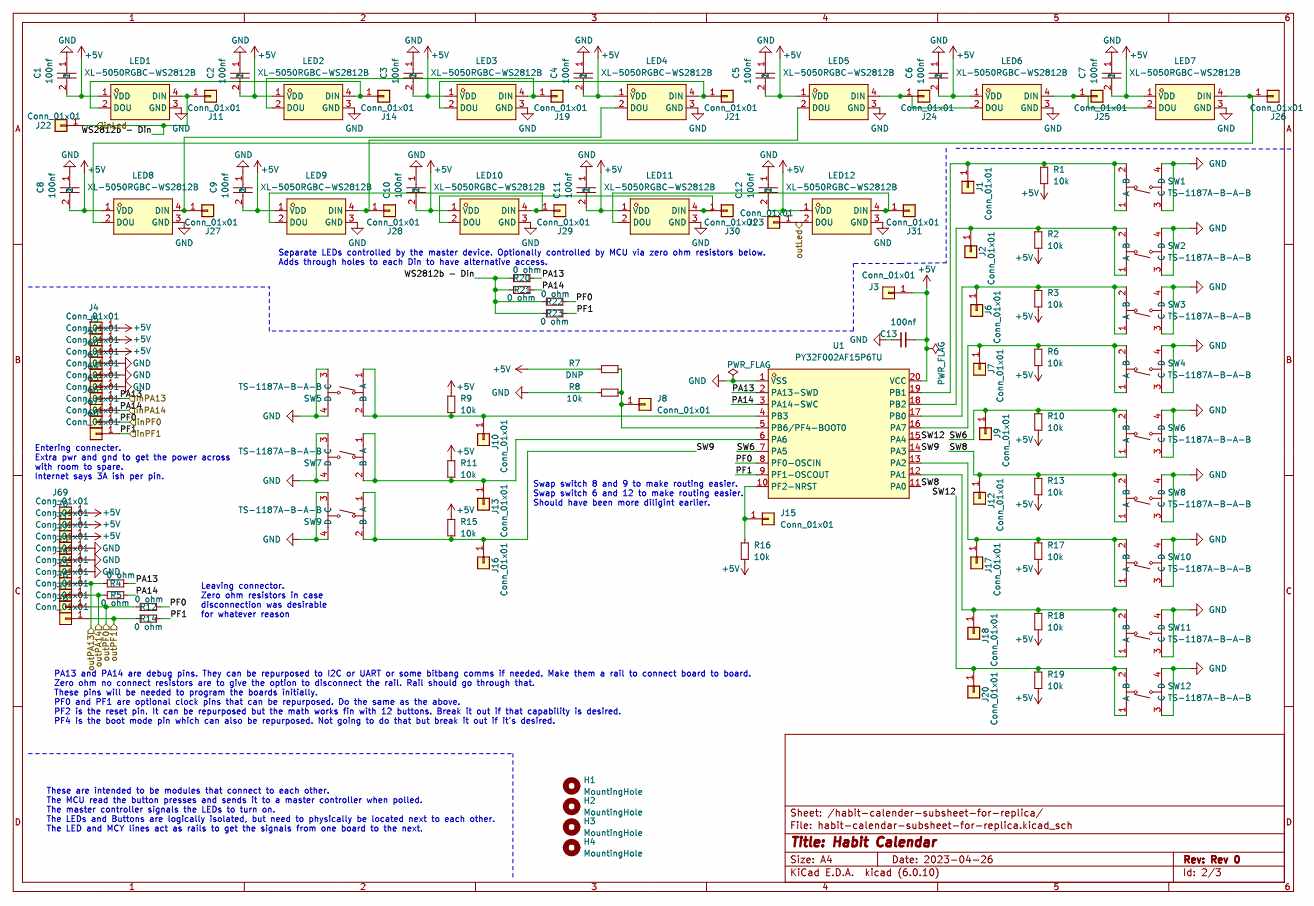

The real (slightly messy) schematic PDF can be found here and seen below.

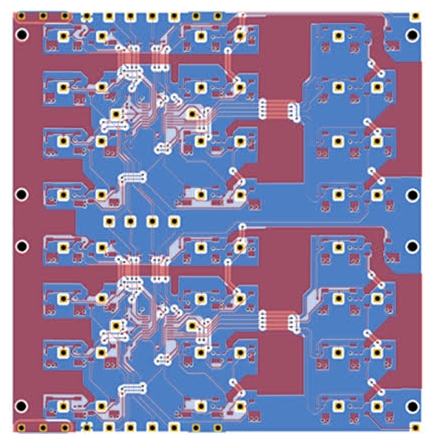

I laid out a board in KiCad and sent it off to JLCPCB to get produced and assembled. Going as cheap as possible meant a 2 layer board with components on one side only.

The board layout PDF can be found here

This board was somewhat annoying to lay out because all the spacing had to be perfect.

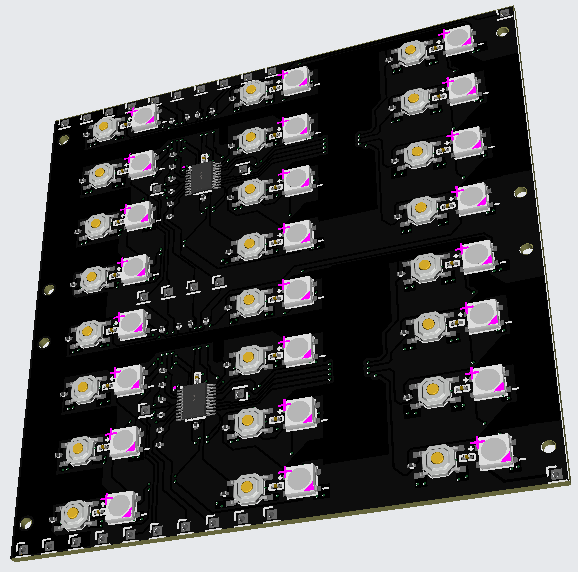

A nice rendering can be seen here:

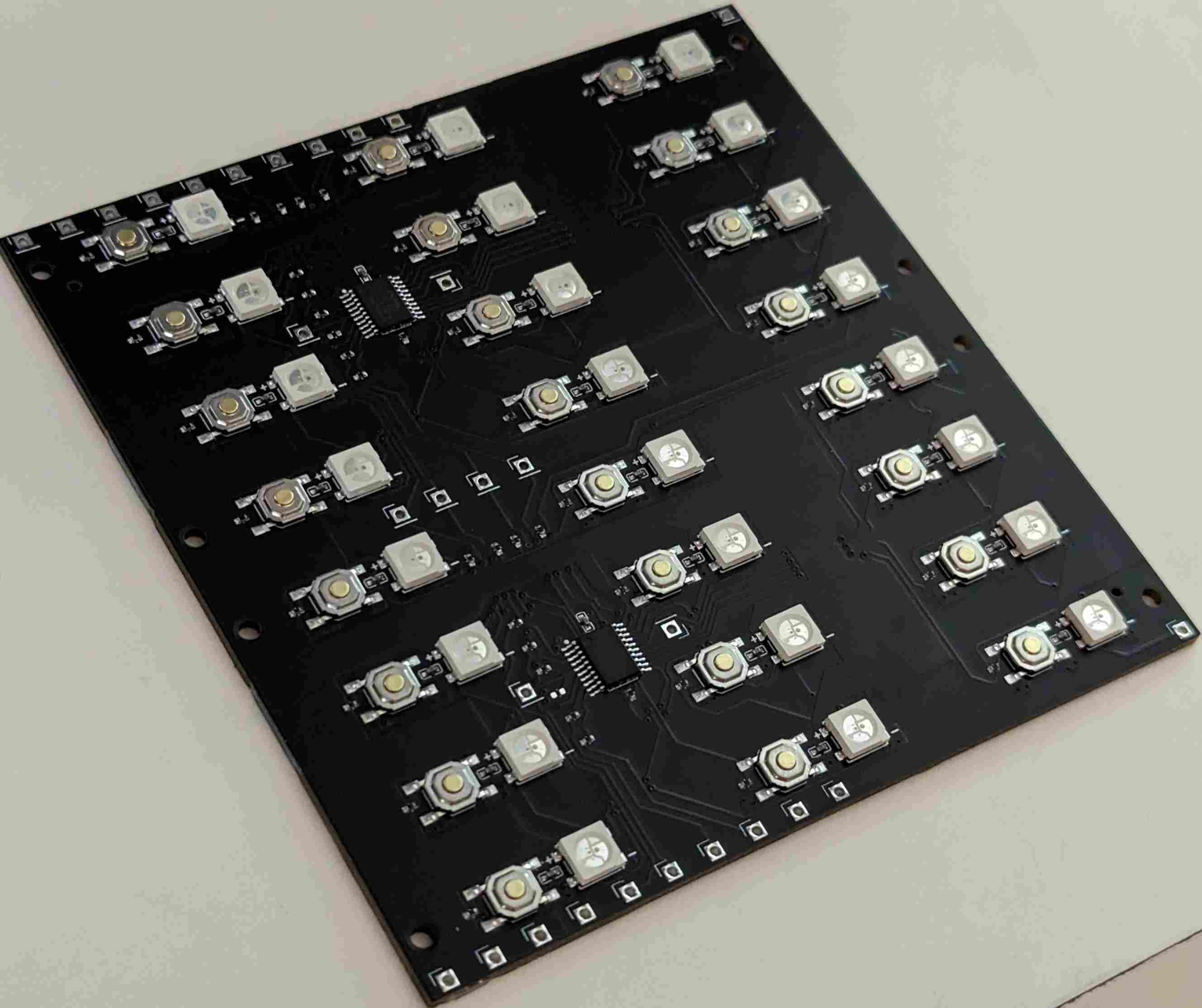

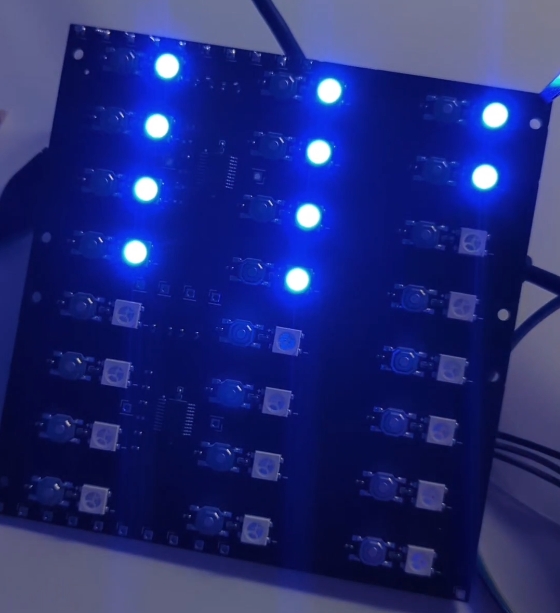

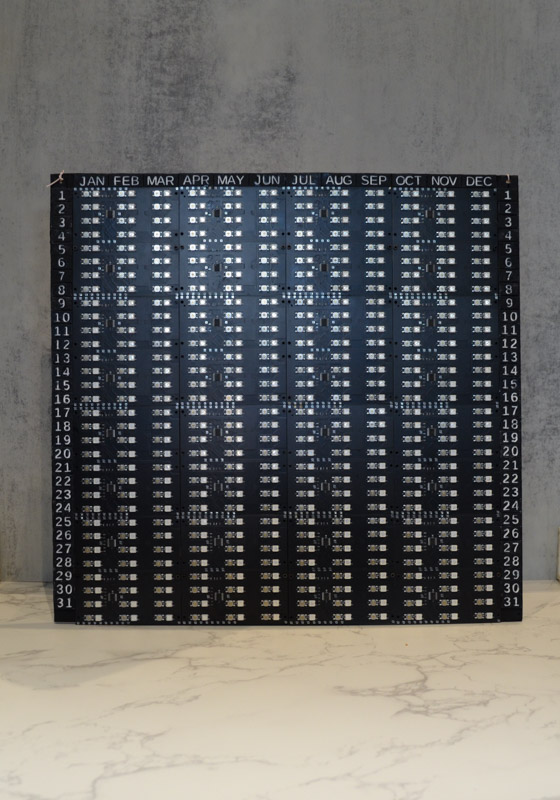

And the actual board can be seen here:

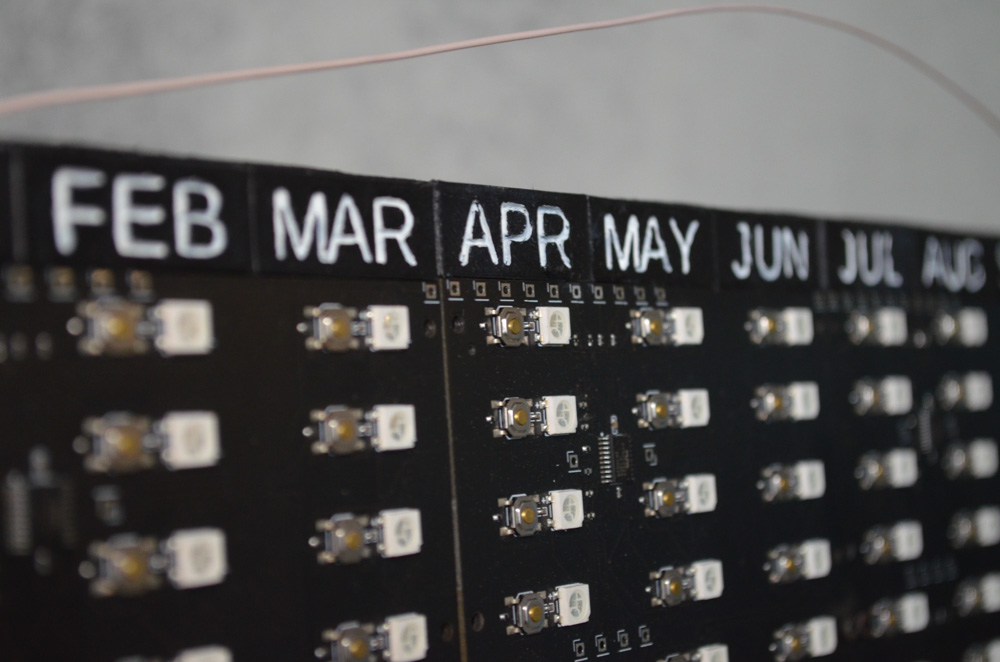

Including shipping, the boards came out to somewhere around $4 each. Each board contained 2 microcontrollers, 24 buttons, and 24 LEDs.

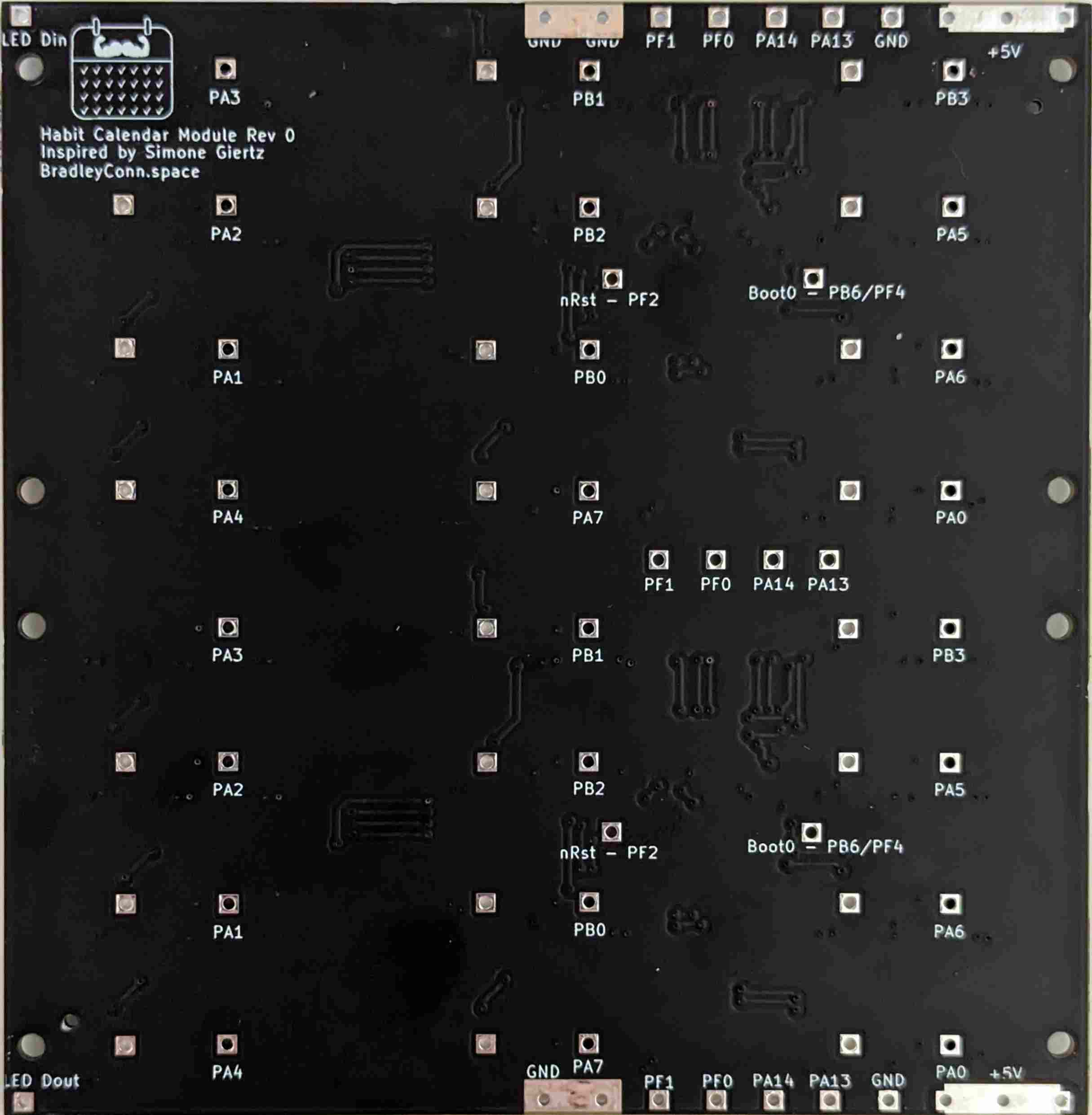

As I’ve never tried the PY32F002A part before, I approached it conservatively and left much room for flexibility. None of the hard function pins (boot, reset, osc_in, osc_out, SWD, SWC) were used as GPIO, meaning only 12 of the 18 GPIO were actually used. These extra pins are broken out and can be used for their intended function as needed or for other requirements if necessary. That is to say, there is room for further optimization. Future versions could also be designed to matrix the buttons, significantly increasing the number of buttons per microcontroller.

One of the design choices I took great delight in was to use zero ohm resistors to enable different configuration options and increase flexibility. For example, a zero-ohm resistor connects the MCU to the LED chain. Should a master controller be desired to drive the LEDs and not the local microcontroller, the resistor can easily be removed.

Each button and LED hides a through hole that can be used for component access. The buttons through holes are electrically attached to the MCU, so they could be removed to have a generic MCU platform with all the pins broken out, albeit on a large board. Similarly, the LED chain is connected through a removable resistor, so it could also be used as a generic LED panel.

The through holes under the button and LED components are the evenly spaced vertical holes in the image below.

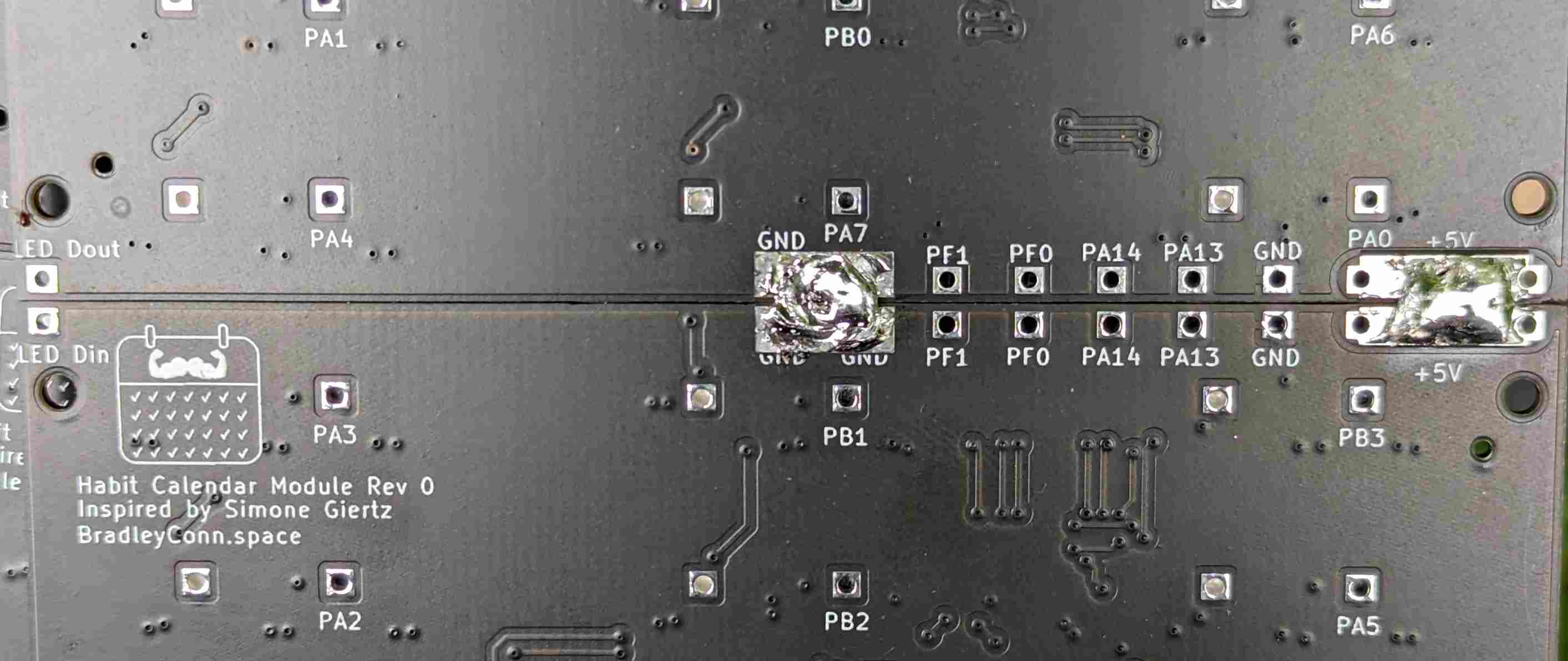

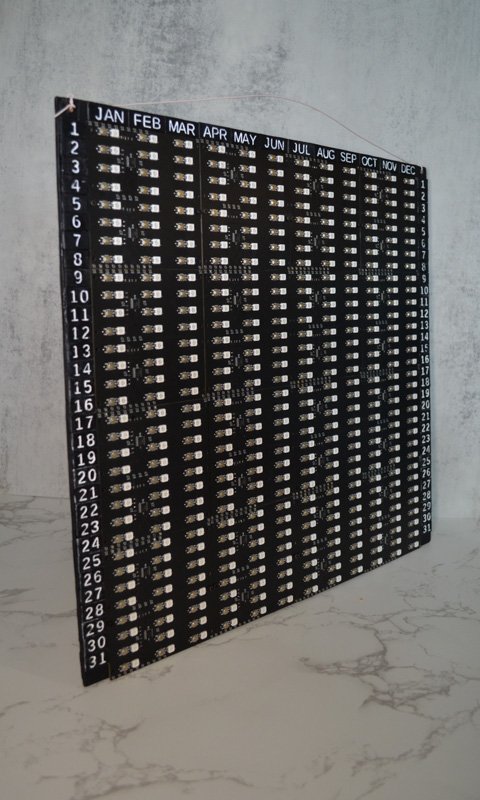

The boards are designed to tile. I wanted to spend as little time soldering as possible so that board connection route out to the top and bottom of the boards. Physically, they are spaced so that they can tile in any direction, but electrically, they can only tile up and down. Power and ground must go through these connections, but the rest may be optional if no master controller is required. The other signals are spaced so they could be connected by standard pin headers. The tile to tile interface worked super well and it is a design I am proud of. The simple tile connection can be seen in the image below. In this image only power and ground connections are needed, but it’s easy to see that each of the signals could be connected with ease.

Software:

After receiving enough boards to complete 3 calendars, it was time to try to bring them to life or find out that I made a mistake and wasted 50 boards.

Thankfully, there’s a Template project for Puya PY32F0 MCU, which Supports the GNU Arm Embedded Toolchain as well as J-Link and DAPLink/PyOCD programmers. It also contains the HAL with some example code.

Trying to get these boards programmed proved to be an annoying activity. Writing this several months after the fact, I won’t be very specific, but I was using a Raspberry Pi Pico as the programmer debugger, so I wasn’t sure if there was an issue with the firmware on that or if there was an issue with the microcontroller. Additionally, the only datasheet in (poorly translated) English was for a different microcontroller in that family and had a different package than I was using. Perhaps there was something wrong with my layout, or I needed to override the boot pin, or my deciphering of the programming pins was incorrect, or there was something wrong with the programming software tool, or I was targeting the wrong chip in the toolchain, or there was a library issue. The PY32F002A is not the standard target for most consumers of the chip, nor is it standard for the template project. As a matter of fact, I could not find evidence of its use anywhere but in my design. In the end, a combination of requiring 3.3v for programming (even though the chip can run off 5v and is what I use in operation) as well as appropriate permissions for pyOCD, the programming tool specified in the Template Project, were the issues.

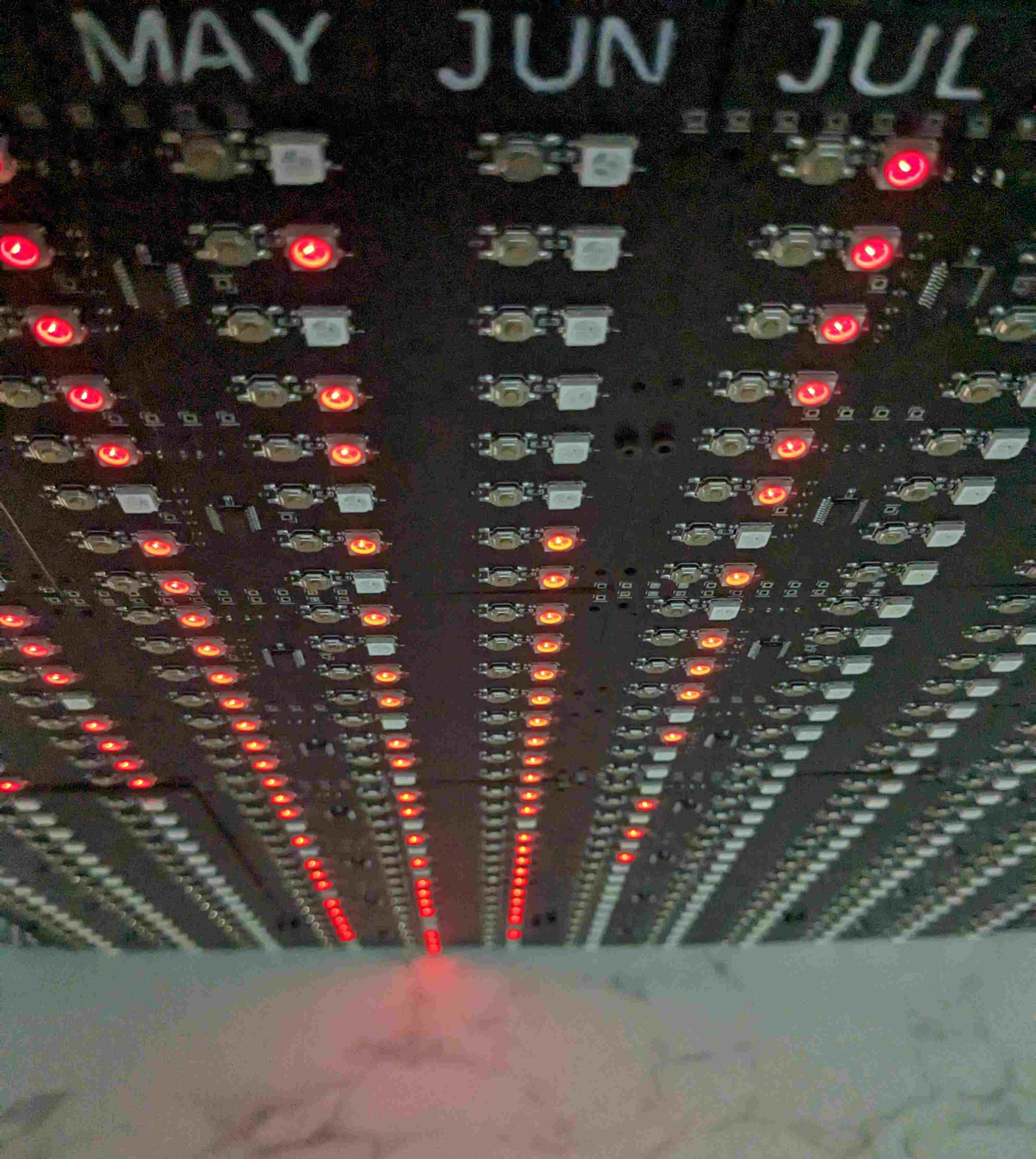

So, I had a microcontroller that I could program, but the debugger was not so much a debugger as it was a flasher in this setup. So, how do you actually verify anything is working? By toggling a GPIO pin, of course! Using the HAL and writing code to turn on a random pin, I programmed the microcontroller and checked with a multimeter, and tada! We’re up and running! From there, I wanted to get the WS2812b LEDs running so I could signal information with that instead of a multimeter. Initially, I wanted to check that it even worked electrically, so I used a Raspberry Pi Pico with WS2812b driver firmware to see if I could light it up, and thankfully, it worked like a charm! Now, to get it to run from the PY32. With a unique communication protocol and tight timing constraints, driving the WS2812b from a slow 8mhz microcontroller without any supporting libraries was a little bit daunting. Using an oscilloscope to dial in the timing, extracting the raw register writes from the HAL, checking to ensure the compiled assembly was optimal, and using function inlining, I was able to bit-bang the protocol at a fast enough rate to drive the LEDs properly. It was quite a delight seeing them light up for the first time! Later, I increased the clock rate to 24 MHz to tune the timing parameters with more granularity. This was more challenging than it should have been with the lack of trustworthy documentation, but it was a joy when it worked.

Next, I implemented the software to read the status of the buttons. For simplicity, polling was used for the first iteration. The main loop was going fast enough that it could probably stay that way, too. At this point, I decided, at least for the first calendar, that I would use the microcontrollers to drive their own LEDs instead of a master controller. This meant that the microcontrollers needed to be able to store the state of each button; otherwise, the calendar would reset on every power cycle. That would be a terrible user experience as the expected duration is to go a whole year before reset. Not to mention, there’s a high likelihood you’d want to turn it off at night or when you’re not around. So, I implemented an internal flash driver and a little table to do that. Then, I decided to add redundancy logic to recover from any possible flash corruption (an issue that plagued me before finding a logic bug).

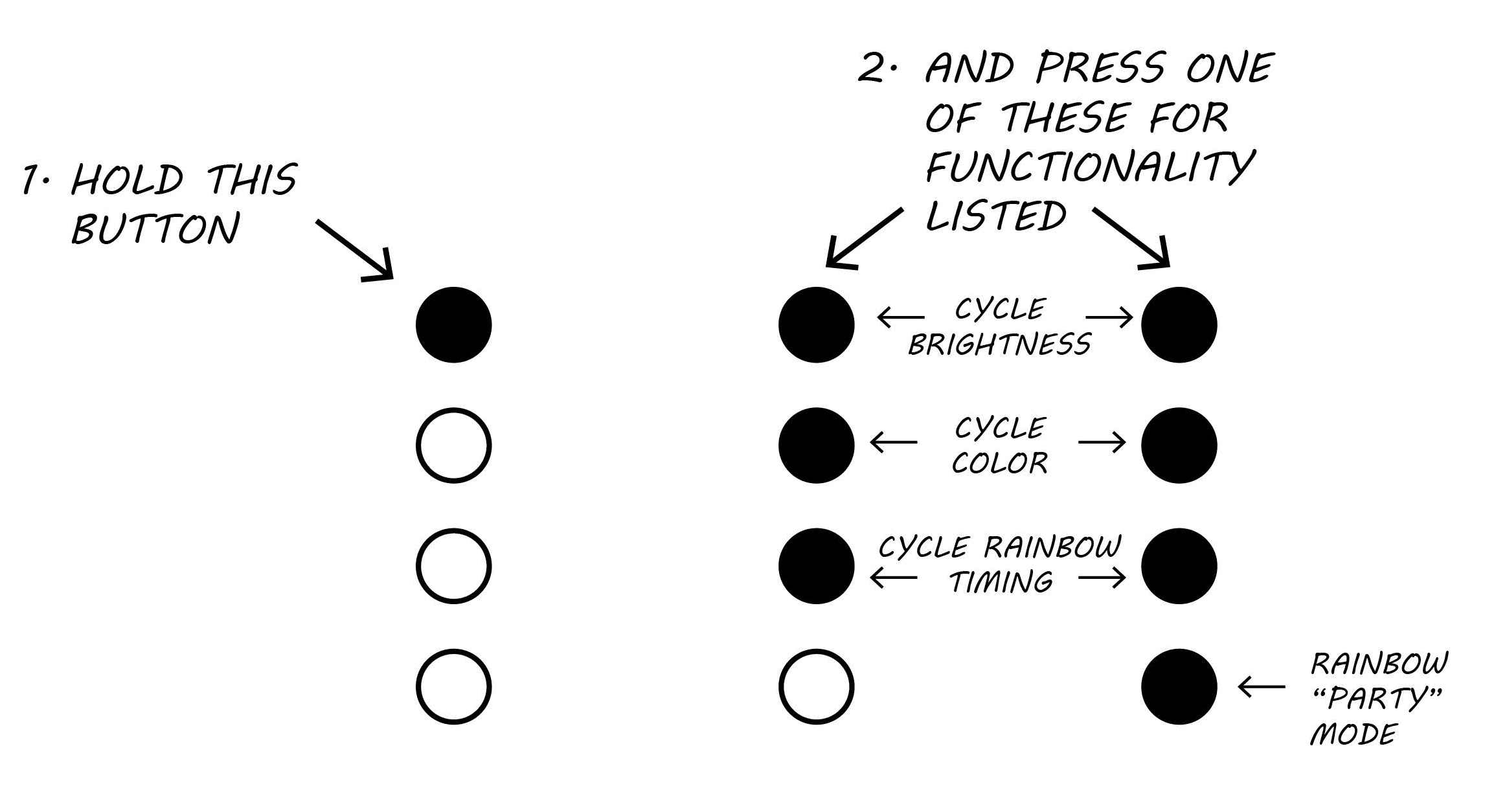

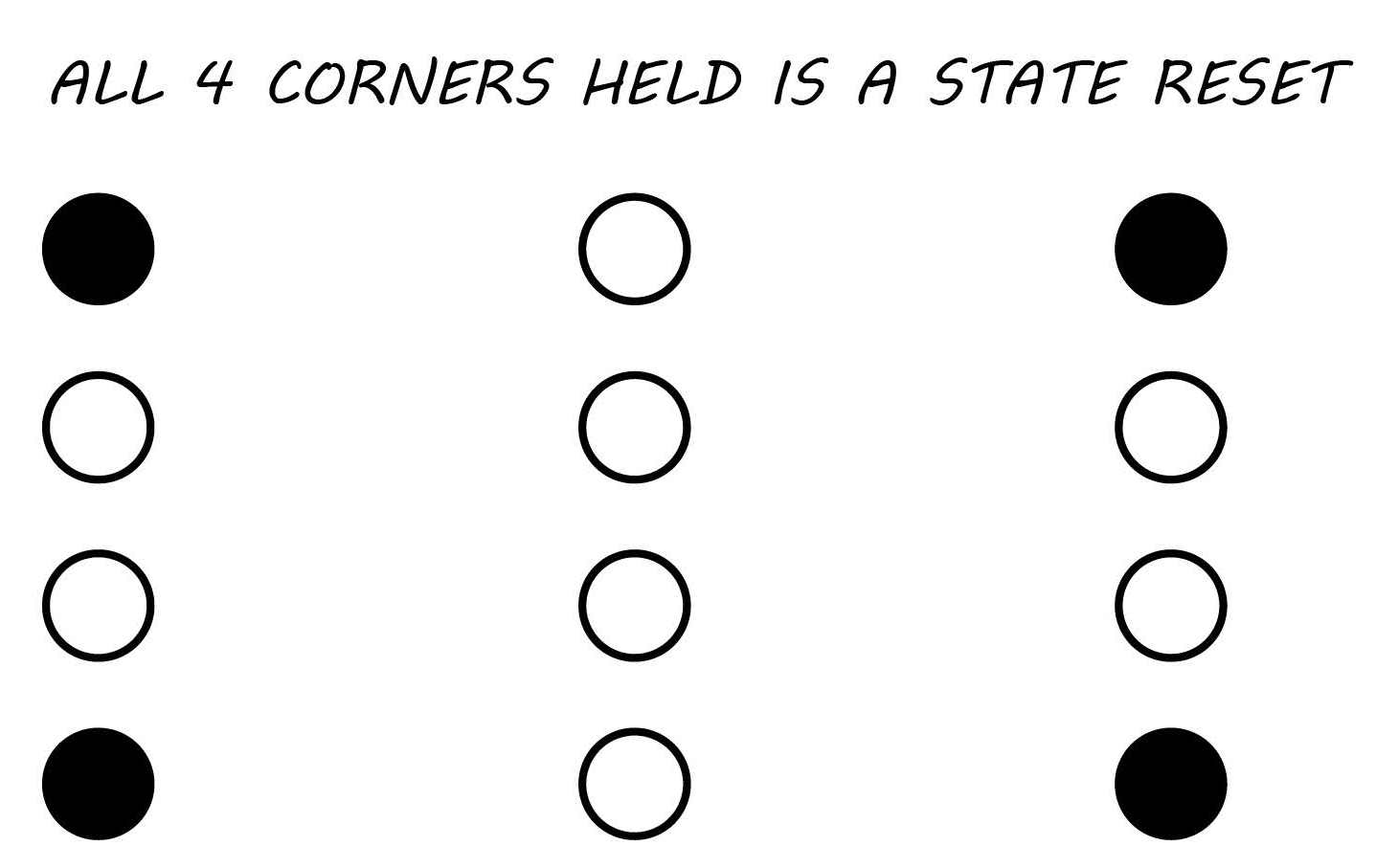

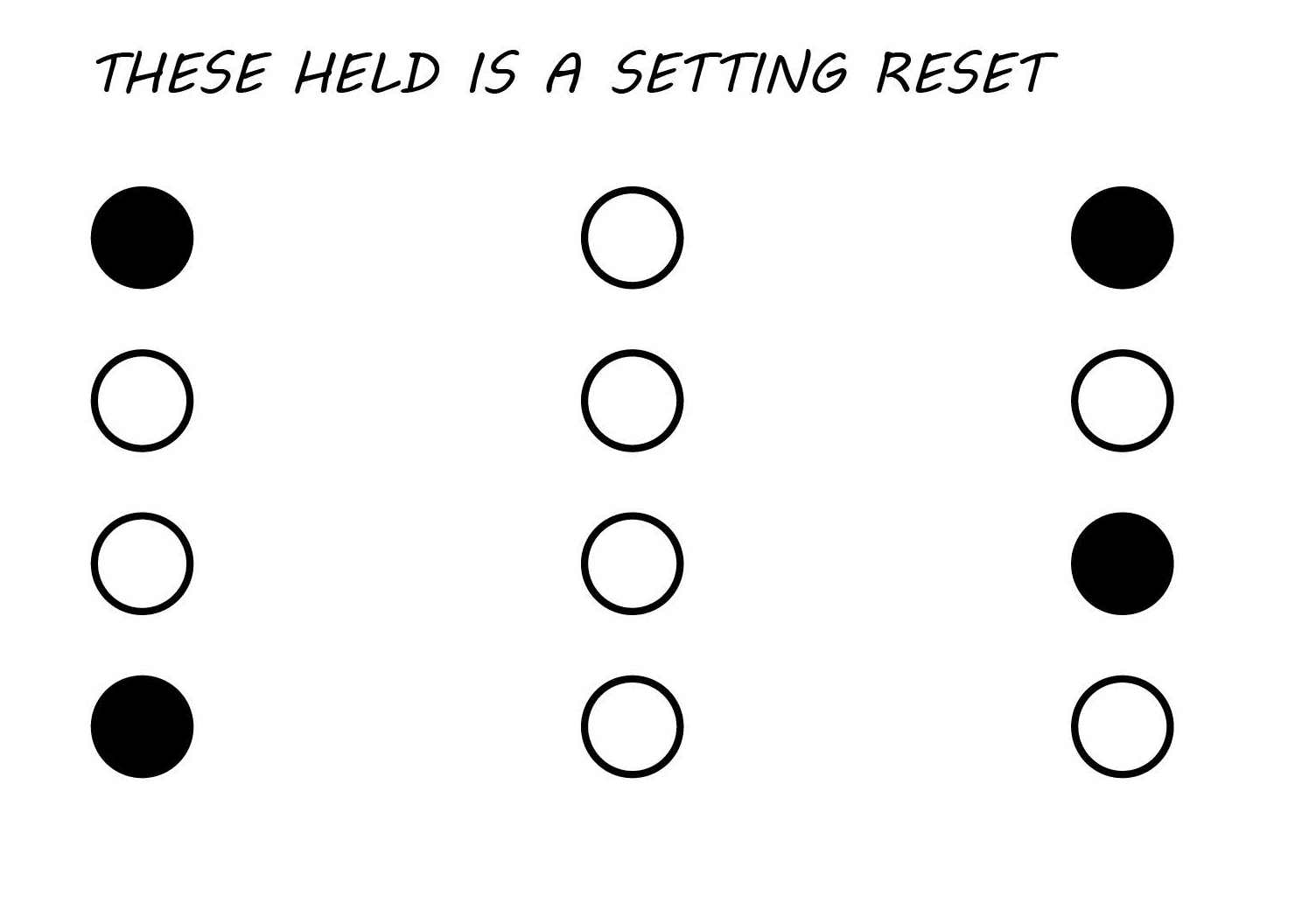

And now, to finish it up, I implemented controls and settings for the LED color and brightness. Holding the top left button while hitting the buttons on the other columns is how to change the settings.

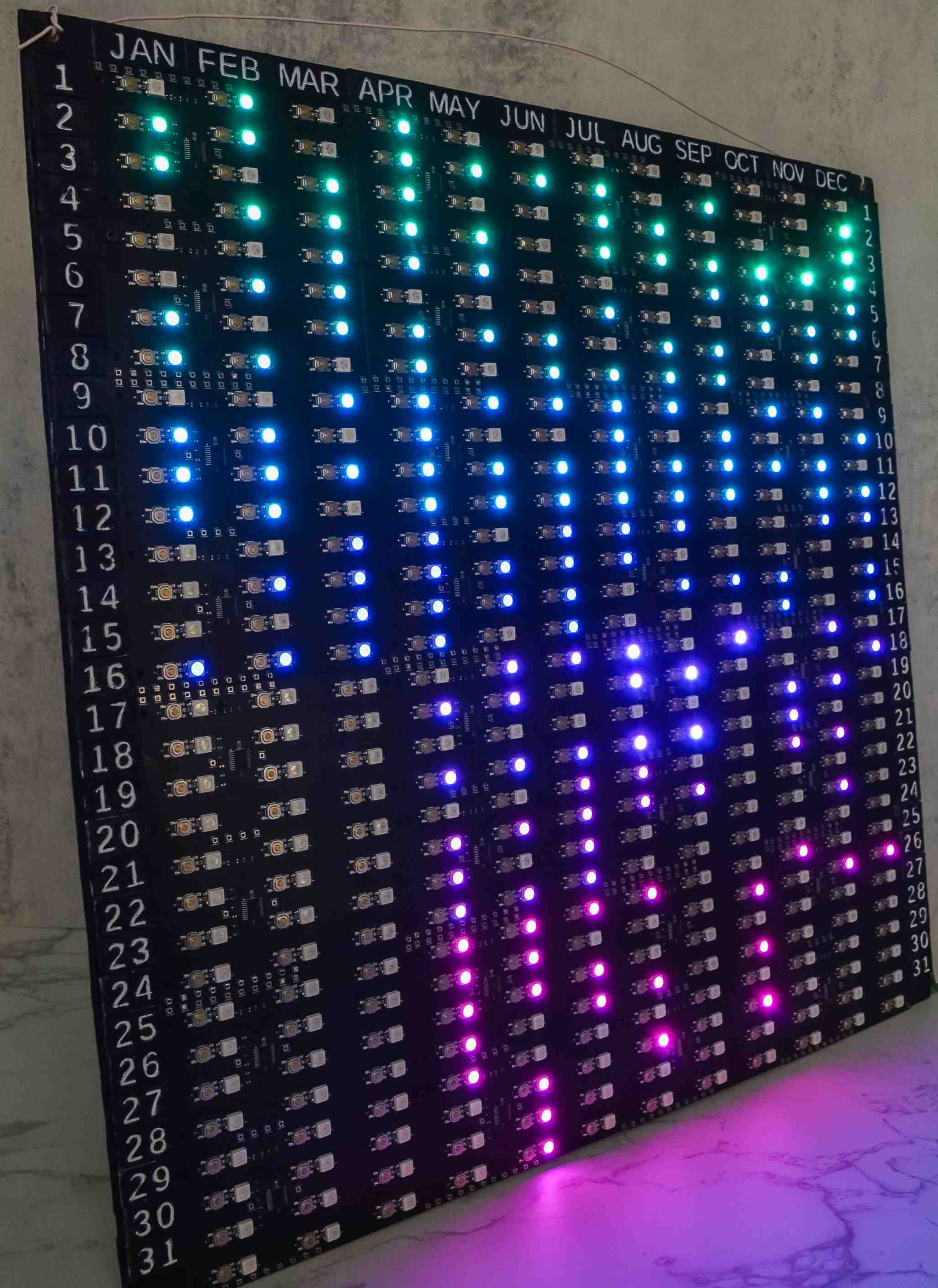

Looking at a static LED calendar was so much less fun than the animation possibility afforded by the WS2812b LEDs! So, I created a “party mode” setting that does a rainbow animation. Additionally, you can change the animation speed. Somewhat more complicated features than it first appears as lower brightness provides less color granularity for a rainbow. Unfortunately, the microcontroller clock speeds vary greatly, so rainbow mode does not work all that well on the full calendar scale, but it’s still fun!

Finally, connecting the tiles together, mounting them on a baseboard, and adding months and day labels finished the project. I honestly hate that it’s square, but that’s that, at least for this PCB rev. Here is the finished calendar!

–

I really like it and I’m pretty proud of it. In the end one calendar cost about $70, with about $20 of that due to shipping. I’d call that a success on the price metric. Now it’s time to consistently maintain a new habit!

P.S. Calendar 2: As mentioned, there are enough tiles to make 3 calendars. So, for the second calendar, a master controller variant is in the works. This version allows color and brightness to change with a simple turn of some knobs instead of annoying to use buttons on 32 different microcontrollers. I hoped to use I2C for all inter-MCU communication, but the TSSOP package does not have I2C slave mode as initially thought. Instead, I created a bitbanged UART implementation for communication. In addition, this version will have a non-calendar mode which will leverage the WLED library for fun animations and wifi connectivity. This will allow the LEDs to be controllable from a companion app. When that is complete, I will try to update it here.